January 2026: An interview with Ben Schneider

QOTM: “I think you can find optimism in any moment if you look hard enough.”

It’s 2026 y’all! Probably past the statute of limitations on wishing everyone a Happy New Year! But I guess I said it anyway.

This should be an exciting, momentous year for rail. For some projects it’s a make or break year. The coming months could be big for safety grants too (remember that killer train in Florida?). And that’s not to mention the huge news that California dropped its lawsuit over the $4 billion of grants that the federal government revoked (more on that later).

Meanwhile, the Rail Revolution brand appears to be growing. No, my unit of measure is not subscriber growth. While at an event in Madison, WI this week, I picked up my name tag. Despite registering as a freelance journalist, I had been given a different title: Rail Revolution Newsletter. (It was a little confusing for other attendees considering I’m in town to report on buses and Madison does not have Amtrak or other rail service, but hopefully soon!)

While I didn’t publish anything on rail or even ride the rails this month (thanks weather), I did something even better. I interviewed the great Ben Schneider, who has been an early friend of this newsletter (check out his Substack The Urban Condition).

The past year has yielded a slew of books on urban issues, headlined by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance. Ben published one of my favorite books in that genre, The Unfinished Metropolis: Igniting the City-Building Revolution. It’s representative of his work, in that it’s wide-ranging, exploring everything from malls to affordable housing to SimCity. I can’t recommend it enough.

In our lightly edited conversation, we largely focus on rail, only veering slightly off track.

Benton Graham: Why write this book now?

Ben Schneider: I wanted to synthesize a lot of what I’ve learned as a journalist covering urban planning for almost a decade now, and aspects of urban planning like Henry Grabar’s Paved Paradise or Alexandra Lange’s book about malls. I was really interested in bringing together these different dimensions of urbanism into one book, and making them part of a single argument. Over the course of writing the book, I became more and more convinced of my argument, which is that American cities have stagnated.

The idea that the built environment has not kept up with our needs is a really important idea that every American should be aware of and should be a discussion point at very high levels of politics and policy and business. All these important fields of endeavor should be aware of the urban situation and how it’s holding us back. That’s the big point that I’m trying to make in the book. I do think it’s really connected to the themes in the book Abundance and other works like that. I hope my book provides more depth in the urban planning arena of that conversation, rather than making a big picture point about America’s inability to build, showing how that has played out in areas like transportation and housing.

BG: When you think of high-speed rail, a lot of that journey is not necessarily happening within a city, but it’s connecting cities. Why is it important to have our cities connected via rail? And how important is high-speed rail to city building?

BS: Rail, and high-speed rail in particular, has the ability to shrink distance between places and create a sense of proximity between disparate cities, whether that’s economically or culturally or in terms of our own relationships with other people. I think this is really evident for people that live on the Northeast Corridor. The way that access to that rail line just makes it so much easier for New Yorkers to go down to Philadelphia or Washington, and vice versa. And have professional connections, have family ties that are just much easier to keep those connections closer. That’s the human dimension of it. As people who read your newsletter are well aware, it’s just a really good form of transportation. It’s a way to move a lot of people very energy efficiently, very quickly, and put them right in the center of town, rather than at an airport that’s an hour outside of the city. Rail has all these benefits that span the personal to the more technical.

BG: In your discussion of the Northeast Corridor, you talked about the psychic benefits of having rail… I think your example was a fun one, of a Flyers fan trying to see the Flyers play the Rangers at [Madison Square Garden], which is extremely convenient to Penn Station. I don’t want you to spoil too much [of your book], but what is it that the Northeast Corridor does so well? Sometimes when I talk with folks about this, they’ll say, ‘It’s just the way that the Northeast Corridor is built, and there’s not really anything for the rest of the country to learn from that.’ I’m curious, are there lessons that the Northeast Corridor has learned that can be applied to other parts of the country?

BS: It’s not an accident that the Northeast Corridor has been the most successful rail corridor in America. It’s the result of over a century of investment in that line as a passenger railroad going back to the early 1900s when a large part of the line was electrified between New Haven and DC. Electrification is still the best way to run a railroad. It allows trains to accelerate faster, have more stops in less time, and, now, we really value the environmental benefits of that as well. So, it was an early electrified railroad, which is really important. They finished electrifying the part between New Haven and Boston when the Acela debuted in the 2000s.

The other thing that railroad has going for it infrastructurally, is that it is almost entirely grade separated. You’re never having to cross roads. It’s always going above or under a road, which is really important for reliability, safety and speed.

Then, a non-infrastructural point, but a really important political aspect of the Northeast Corridor, is that it’s entirely owned by Amtrak. Amtrak gets to decide when and how freight trains use the line, and it gets to decide when construction work happens. It’s in control, and therefore it’s able to make decisions that benefit passenger rail. That’s not the case almost anywhere else in the States where freight companies own the underlying track. They’re making the decisions about which trains can go when, and also the larger scale decisions about how to develop that infrastructure, or to let it wither.

BG: As someone who uses Amtrak from Richmond to travel into the Northeast Corridor, it’s quite annoying to go north of DC, because you have to wait for them to change engines for 45 minutes.

I appreciate you also mentioning the ownership piece of this. It’s not just Amtrak anymore. We have Brightline as well. Do you see a path to greater ownership by passenger rail companies, or is it inevitable that you have to work with the freight companies?

BS: There’s some low hanging fruit in terms of the lines that are largely owned by state governments or Amtrak. There are a few others besides Northeast Corridor. A lot of Virginia’s network, for example, is state-owned. The New York-Albany stretch is state-owned. A lot of the Pennsylvania lines as well. A lot of Southern California. There are these places where the government actually does actually own the tracks. If the state governments there were thinking seriously about rail, they could invest even further. That is really happening in Virginia, I should give them credit, and somewhat in New York. There’s definitely a lot more that can be done with the existing state-owned stretches of track to make those railroads more like the Northeast Corridor infrastructurally.

Generally speaking, you’re right that passenger rail in the US for the foreseeable future is going to have to work closely with the freight railroads that do own a lot of the tracks, and, even when there are state-owned sections of track, it often isn’t the entire route between two major cities. You can make some changes on the state-owned part, but you still have to negotiate with the freight operator for that next section of it. It’s a complicated and important relationship that will need to be managed for the foreseeable future.

One interesting thing on the horizon, in terms of how that could play out, are the mergers that are expected between some of the major freight rail companies and what kinds of trackage rights could be negotiated, or if those companies just decide to prioritize certain geographies. Can passenger rail get more opportunities to purchase tracks, or states have more opportunities to purchase tracks through those mergers that are on the horizon? It’s something that I’ve heard other rail wonks speculate about. No one really knows what would actually happen, but there’s a potential opening there for some new relationships, new deals to be made.

BG: Let’s shift to California. You write that the California High Speed Rail project is ‘in a class of its own’ when it comes to over-promising. This is probably hard to sum up in a few words, but why has that project struggled so much?

BS: California High Speed Rail is the epitome of an everything bagel to use Ezra Klein’s Abundance parlance. It really was trying to be all things to all people as a project, starting from its inception and, especially, with the voter initiative in 2008 that created the $9 billion bond that initially funded the project. The stipulations put on the project at that point were extremely constrictive and extremely difficult to meet. Part of that is the route geography itself, which basically seeks to hit every major population center between San Francisco and LA, rather than going the most direct route between the core of the Bay Area and the LA area, which politically makes sense, but in terms of the cost of the project and the complexity that made it much more difficult.

Then there are the environmental rules that have to be followed to just get the plans approved. That is extremely expensive, time-consuming, [and] litigious. Connected to that, the eminent domain battles that were waged. That’s also connected to the route itself, where, because they were not choosing interstate adjacent routes usually, or other state-owned corridors, they were having to buy a ton of land from farmers and landowners that didn’t want to sell it. There are these cascading complexities that made the project harder than anyone would have wanted if they were just trying to plan it from scratch.

BG: Some recent documents coming out of the California High Speed Rail Authority suggest they’ll start by going to a place like Gilroy, or someplace closer to Silicon Valley. Do you think there’s still an opportunity for this project to reconfigure how it gets off the ground? Or does it feel like it’s still locked into what it presented voters in 2008?

BS: There are definitely some opportunities to address those issues that I’ve talked about. I think there’s been a reckoning in the last couple years, very belatedly, about some of the issues that I just identified. For instance, now it’s exempted from environmental review for station construction, which is a small step forward in addressing that larger environmental review question. They also just did a value engineering revision of the project. Another thing I didn’t even mention before is that the project was supposed to be a truly state of the art, fastest-in-the-world high-speed rail system with the most advanced engineering requirements. One of the things that the Authority has been doing recently is rethinking that and looking at how can you make it good enough, rather than the best in the world, the fastest-in-the-world? That’s another area where they’re potentially looking to make things a little easier on themselves.

Then the routing question, the initial segment that they’re constructing right now between Merced and Bakersfield in the Central Valley has never really been a super promising corridor in terms of ridership and revenue. The current leadership of High Speed Rail is recognizing that. They’re saying, we could maybe bring in a private partner to help us pay for this and operate it, if we serve a corridor that has more ridership potential. That’s where those conversations are coming in. Maybe the first step has to be to get this thing to the Bay Area, instead of focusing just on that Central Valley segment, all on its own. That appears to be moving forward as a concept. That’s another way the project is trying to transcend some of these initial constraints that were put on it.

BG: You are from California, right?

BS: Yes.

BG: I know there’s some polling that seems to show that it’s still popular. When you go home or talk to friends or people in California, do you get the sense that that’s true? Are people still like, ‘Yeah, let’s do this,’ or is it kind of like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is feeling like it’s never gonna happen’?

BS: People in California are Democrats overwhelmingly, and are pretty conceptually in favor of trains and public transit. Especially something like a high tech bullet train is a really exciting thing that a lot of people like the sound of. But there’s definitely a growing fatigue of this project. The way that it has actually played out, and the promises that have not been kept around how much it was going to cost and when it would be done. That’s a big challenge for the project to keep momentum when people are losing some faith, losing some patience in a thing that there’s legitimate fear will never happen. There needs to be some strong sign that it will. That would be important for the project to win the public relations war. It’s quite possible there will need to be another ballot measure at some point to provide some more funding to complete it between SF and LA. In that case, there definitely would need to be outreach to voters and the public to explain what’s happening and show that it’s actually going to work.

BG: Speaking of funding, the state announced that it was dropping its lawsuit on the federal government’s decision to revoke a couple billion dollars in grants, which was an interesting decision given that this is a very expensive project. Were you surprised by the state’s decision? What do you think that means for the future of the project?

BS: I wasn’t too surprised by it. There was a fear that it would be hard for California to win it. If, in fact, they win that lawsuit against the federal government about them revoking this money, because the federal grants are for that Merced-Bakersfield segment, if they say, we’re actually tabling that vision, it’s a hard legal case to make that they’re entitled to that money. In that sense, it’s not so surprising that they’re giving up. Obviously, the statements they’ve made about it are very logical. The federal government has not been a reliable partner on this, particularly under Trump. I don’t think there’s much that they can lose from this move in the near term, politically. The money is getting revoked anyway it seems like. Obviously, $4 billion is a huge number. It’s never a good thing for a major project to lose $4 billion, but, in some ways, it creates a little more flexibility for this project to make the pivot that it’s trying to make in terms of the routing, and to commit to the strategy of being internally funded via the state and potential private sector partners. It makes that path a little more clear, in a way. It’s a bit of a complicated situation, but there is a certain logic to it.

BG: You point out a lot of the ways how we’ve fallen as a country when it comes to city building. The current administration has been pretty adversarial when it comes to working with city governments, but you also throughout [the book] are presenting some pretty cool solutions. It does seem like there’s an energy around city building that’s fresh in the last decade or so. Do you see this as a moment that’s optimistic in terms of improving our urban infrastructure or not? If so, why do you think it’s a moment for optimism?

BS: I think you can find optimism in any moment if you look hard enough. There are bright spots around certain aspects of urbanism and city building. An example I turn to a lot is the street redesign movement. I think this is something people take for granted, the extent to which city streets have been totally transformed in recent years by bike lanes and bus lanes and outdoor dining. Bikeshare itself, both the racks and then the number of bikes and scooters that have been put on the streets by those programs, that’s a huge transformation that is ongoing and has changed cities for the better and has created this new way of getting around for a lot of people that never would have considered biking before, [and] that now feel much safer walking. Buses are more reliable and faster. That’s really happening in cities across the country, and it’s gratifying to see that and important to call it out as an actual transformation that’s happening.

The zoning reform movement is really happening too. That’s in the policy weeds. Every step forward with zoning reform, you seem to need to make a bunch of cleanup legislation to close the loopholes. It’s a hard thing to actually fix a century of bad zoning policies, but, generally speaking, things are moving in the right direction in a lot of places around zoning policy, getting better and more geared towards allowing the housing that we really need in cities.

The reality [is] that this is happening in front of a federal government that is completely disinterested, or, as you say, openly hostile to urban issues. That’s especially the case when it comes to large chunks of money to fund major infrastructure projects, whether it’s something like California High Speed Rail, or major subway expansions in cities, or improvements to public housing or other affordable housing programs. Those things are generally going to be moving in the wrong direction under the status quo, and I think that’s an area where, over the long term, it would be really exciting and important for people that care about these issues to strategize and think about how big an appeal to people across the country, to people across the political spectrum to make these big investments in cities and urban infrastructure. It’s a generational challenge that is really important.

Did I ride rail?

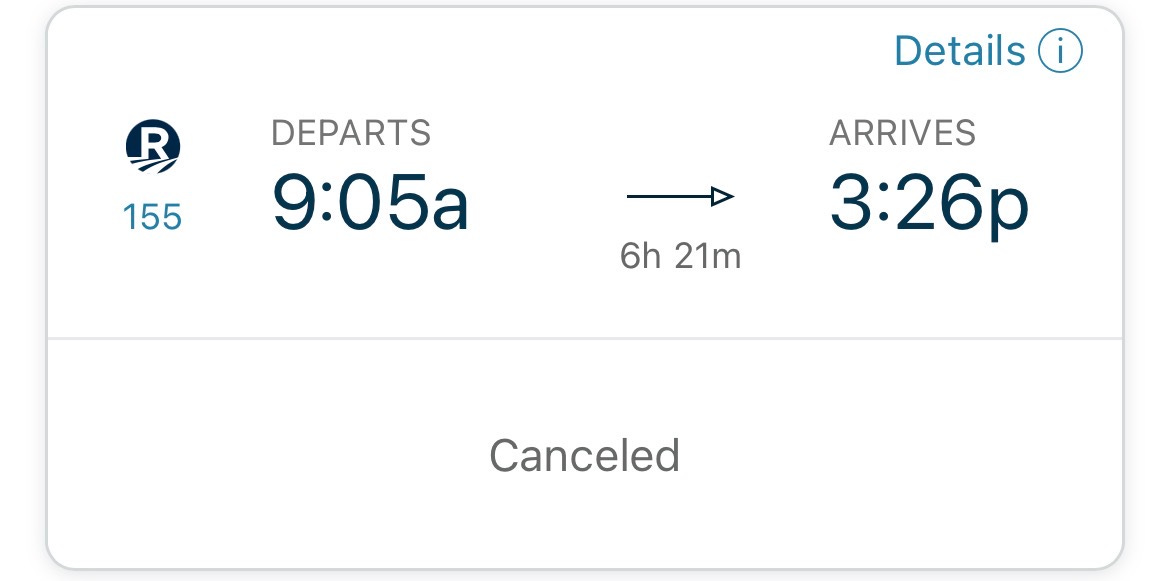

Winter Storm Fern got in the way of a NextGen Acela (my wife and I) vs. NE Regional (my brother-in-law) train race from DC to NYC. I also had plans of training from NYC to Richmond (evidence below) but alas.

In better news, I am a member of the #RailRatArmy after my sister used the site to monitor her Palmetto train taking her from Richmond to DC on the cusp of the storm.

Did I publish a story about rail?

Nope :(

Three things I’m reading

AP - California drops lawsuit seeking to reinstate federal funding for the state’s bullet train

California dropped major news that it won’t fight the federal government on a $4 billion grant any longer. The project will now rely on state and possibly private sector money. A spokesperson for the project said the federal government is not a “reliable, constructive, or trustworthy partner.” Here’s my story from September for a little more context.

The New York Times - Travel Math: When Flying Costs as Much as the Train, Who Wins?

A look at why it increasingly pays to book Amtrak tickets early thanks to the company’s dynamic pricing.

BBC - What we know about Spain's worst rail disaster in over a decade

A tragic crash in Spain, the country with the world’s second largest high-speed rail network, killed more than 40 people. Investigators are still looking into the cause, though it appears the rail had been damaged.

Special thanks to David Graham and Ariel Quintana for their edits.